The Race Against Time: Stopping H5N1 Before Human to Human Transmission. Is Your Steak Safe? The H5N1 Threat Explained

The Case for Comprehensive Testing.

If there is a possibility of preventing a pandemic, every conceivable effort must be made to avert the catastrophic consequences that could follow. Pandemics not only cause widespread illness and death but also bring about untold suffering and profound economic loss. The impact on public health can be devastating, overwhelming healthcare systems, and leading to a high mortality rate, particularly among the most vulnerable populations. The ripple effects extend far beyond the immediate health crisis, affecting mental health, social stability, and overall quality of life. Preventing a pandemic is not just a matter of public health—it is a moral imperative to protect human life and dignity. We should have already learned this lesson from COVID-19 but clearly, our governments and public health agencies haven’t learned it yet.

Economic losses during a pandemic can be staggering. Business closures, job losses, and a decline in consumer confidence can lead to prolonged economic downturns. The burden falls heaviest on small businesses and low-income workers, exacerbating inequality and poverty. The global economy becomes interlinked, and disruptions in one region can have far-reaching effects worldwide. By investing in preventive measures, such as robust testing, effective containment strategies, and comprehensive vaccination programs, we can mitigate these economic impacts. The cost of prevention is a fraction of the economic toll a pandemic would take, making it not only a compassionate choice but also a financially prudent one.

The potential dangers to children and their future add another layer of urgency to pandemic prevention. Children are not just passive victims; they are the future of our society. Pandemics can disrupt education, leading to long-term setbacks in learning and development. The psychological toll on children can be severe, with increased anxiety, depression, and trauma from losing loved ones or experiencing prolonged isolation. By preventing a pandemic, we are safeguarding the mental and physical well-being of our children and ensuring they have the opportunity to grow up in a stable and secure environment.

Preventing a pandemic is an investment in our collective future. It is about preserving lives, maintaining economic stability, and protecting the well-being of our children. Every effort made in prevention today will pay dividends in avoiding the immense suffering and loss that would accompany a global health crisis. It is our responsibility to act decisively and proactively, harnessing all available resources and knowledge to avert such a disaster. The stakes are too high to do anything less.

The USDA recently completed testing muscle (meat) samples from a limited number of dairy cows, revealing that 1 out of 96 samples tested positive for H5N1. This finding suggests a potential infection rate of 1%, highlighting the need for more extensive testing to accurately determine the scope of the issue. With approximately 3 million dairy cows culled annually in the United States for meat production—about 57,692 cows weekly—it is concerning that hundreds of infected cows could potentially enter the meat supply each week without additional testing. Notably, rare-cooked meat may not kill all the virus, posing a risk of exposure, and thus viral evolution in humans. We’ll break down the details of the latest data.

There is some good news released from the recently released epidemiological data. The reports tell us that the genomic or epidemiologic evidence does not support that wild birds are spreading H5N1 to cattle. This means that, with prompt action and the implementation of effective testing and containment strategies, it is possible to contain outbreaks among cows, thus reducing the risk of human exposure and viral evolution.

They highlight that 80% of the infected farms have cats, many of which are infected and dying. Unfortunately, a sudden increase in sick or dead cats serves as an indicator of the virus's presence on a farm. Additionally, they identify a significant number of people who frequently make visits to more than one farm could be a risk factor for spreading the virus between cows. These findings should prompt the CDC to regularly test all of the people identified to isolate any positive cases to prevent the emergence of a new variant capable of human-to-human transmission.

We will dive into the details of these reports, and discuss the implications for containment and the prevention of a potential human-to-human transmission event, which could trigger another serious pandemic.

Immediate access to paid subscribers.

By subscribing, you’re helping support unbiased reporting: TACT cuts through the noise and delivers critical information you need to make informed decisions about your health.

Testing of Dairy Cows Entering the Meat Market

The USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) tested 96 cows at select facilities, and while viral particles were detected in one cow, the remaining 95 samples tested negative. FSIS concluded that the beef supply is safe after testing for the H5N1 virus in beef tissue from cull dairy cows, however, this assessment has a huge problem. This testing prevented one cow from entering the meat supply, which supports widespread testing. This is the only testing that has been done and it was on a very small sample size.

According to the USDA, the Federal Order does not apply to the intrastate movement of a lactating dairy cow to a sale barn or the subsequent interstate movement for a lactating dairy cow from a sale barn directly to a slaughter facility. It requires only a Certificate of Veterinary Inspection (CVI) stating that the animal is clinically healthy however there is no testing necessary. There is no in-state testing required and interstate testing only applies to lactating dairy cows. In other words, it does not apply to calves, non-lactating dairy cows, or beef cows. Based on this, it is very likely that a large quantity will end up entering the meat supply.

To date, testing has been completed on 96 out of 109 muscle samples that were collected. As of May 22, no viral particles were detected in 95 samples for which testing has been completed. Viral particles were detected in tissue samples, including diaphragm muscle, from one cow.

FSIS and APHIS are working together to conduct traceback, including notification to the producer to gather further information.

FSIS personnel identified signs of illness in the positive animal during post-mortem inspection and prevented the animal from entering the food supply – as is standard for the food inspection process. This testing prevented one cow from entering the meat supply, however, this is the only testing that has been done so it is very likely that a large quantity will end up entering the meat supply.

Ground beef cooking study: Final results were posted on May 16, 2024. ARS inoculated a very high level of an H5N1 Influenza A virus into 300 grams of ground beef patties (burger patties are usually 113 grams) to determine whether FSIS recommended cooking temperatures are effective in inactivating H5N1 virus. The burger patties were then cooked to three different temperatures (120, 145, and 160 degrees Fahrenheit), and virus presence was measured after cooking.

There was no virus present in the burgers cooked to 145 (medium) or 160 (well done) degrees, which is the FSIS’ recommended cooking temperature. Even cooking burgers to 120 (rare) degrees, which is below the recommended temperature, inactivated much of the virus, but not all the virus.

https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2024/05/24/updates-h5n1-beef-safety-studies#:~:text=To%20date%2C%20testing%20has%20been,diaphragm%20muscle%2C%20from%20one%20cow.

Epidemiologic Brief Posted June 13, 2024, by the USDA

APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) put out an epidemiological brief updated through June 8, 2024. They confirmed the detection as HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, genotype B3.13 in cows.

Key Messages of the Report:

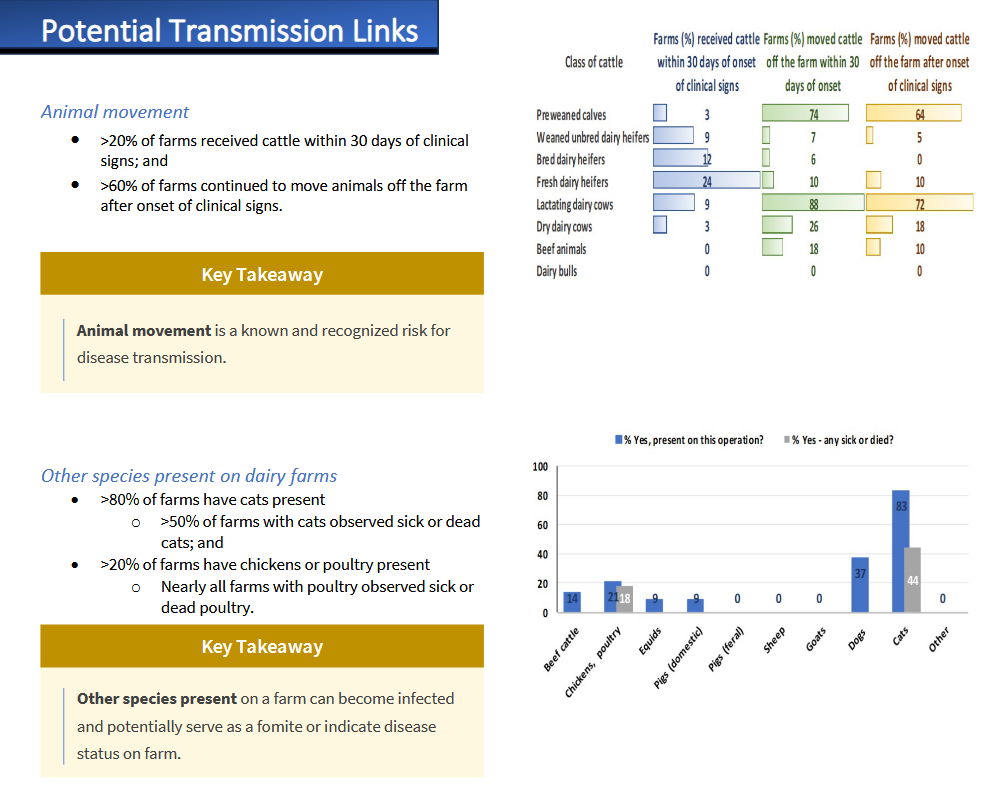

The spread of H5N1 between states is linked to cattle movements (versus independent wild bird introduction) with further local spread between dairy farms in some states.

Disease spread between dairy cattle farms is likely multi-factorial (direct and indirect transmission routes).

Biosecurity is key to mitigating the risk of disease spread.

Epidemiologic information is currently available for 54% of confirmed premises.

No genomic or epidemiologic evidence that wild birds are spreading H5N1 to cattle but cannot be ruled out.

Other species present on dairy farms

>80% of farms have cats present

>50% of farms with cats observed sick or dead cats; and

>20% of farms have chickens or poultry present. Nearly all farms with poultry observed sick or dead poultry.

Shared personnel are a recognized risk for disease transmission.

Shared Personnel

• >20% of dairies’ employees visit other dairies within 30 days of the onset of clinical signs;

• >20% of dairies’ employees own livestock or poultry at their personal residence;

• >30% of dairies’ employees work at another farm with livestock; most of these employees work on another dairy; and

• 20% of dairies’ employees have family members who work at another farm with livestock.

Frequent visitors with access to animals are a recognized risk for disease transmission.

Support Services

• >60% of affected farms have regular visitors who have contact with cattle; and

- Veterinarians

- Nutritionists/feed consultants

- Contract haulers

- Hoof trimmers

• >40% of farms use renderers and breeding technicians.

- Frequent visitors

- Most have contact with cattle

Clinical Observations

• >80% of farms report abnormal lactation and decreased feed consumption; and,

• >90% of farms reported thickened or clotted milk.

Spread the word about TACT to a friend and contribute to keeping more people informed about the latest information.

TACT’s Assessment:

H5N1 poses a significant public health risk by exposing the virus to thousands of farm workers and their families. The more people the virus can infect, the greater the likelihood it will evolve to adapt to humans and eventually gain the ability to spread from person to person. Both the above epidemiological report and the Michigan report also released on June 13, 2024, highlight the large number of people in direct contact with infected cows, identifying these individuals as a risk for disease transmission.

Given these findings, the CDC should initiate regular testing of all individuals identified in these reports, as well as those working in slaughterhouses who come into contact with infected animals. It is crucial to mandate the isolation of people who test positive and to test their household members before ending isolation. This strategy ensures that any virus potentially evolving to spread between humans is quickly contained and eradicated.

If for some reason, the CDC can’t lawfully test people who don’t want to be tested or are prevented by the dairy industry or state officials then as a backup to testing individuals, they could rapidly increase H5N1-specific wastewater testing throughout the U.S., starting with the areas around all of the infected farms.

Furthermore, the FDA should require the expanded testing of all cows involved in interstate transport, while closing the current loophole for dairy cows sent to sales barns. The USDA must enhance random testing of calves and both beef and dairy cows before in-state travel. These measures are essential for containing the virus's spread among cows. According to both the genomic and epidemiological data, the disease is not being introduced by migratory birds but is spreading between cows. This indicates that we have the capacity to halt this transmission in cows and prevent tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of human exposures in the future. Reducing human exposure decreases the chances of the virus evolving to spread between people.

Understanding that this is primarily spreading between cows and not caused by birds provides us a huge advantage. By curbing transmission between cows, and containing the outbreaks, we can alleviate the burden on the CDC for testing and isolation. This comprehensive strategy would enable a return to normalcy while protecting everyone’s safety, and the economic security of the country while preventing a worldwide pandemic. After the outbreaks are contained, we would need to maintain enhanced testing for interstate cattle movement to quickly detect and contain any new outbreaks.

The crucial question is whether the Biden administration, along with the CDC, FDA, and USDA, will implement these necessary measures to prevent human-to-human transmission and another pandemic. Swift action is vital. The more the virus spreads, the harder and more expensive it becomes to contain.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with new immune-evasive and suppressive variants gaining momentum, provides H5N1 opportunities to infect people and evolve within those recently or currently infected with COVID-19. If things progress as they have been going, then we are likely facing an inevitable evolution of H5N1 to spread from human to human. We have an uncertain window of time to contain this before that happens. This is predictable. This is preventable.

"Severe pneumonia with co-infection of H5N1 and SARS-CoV-2: a case report"

Case presentation:

"A 52-year-old woman presented with a fever, which has persisted for the past eight days, along with worsening shortness of breath and decreased blood pressure. Computed tomography (CT) revealed an air bronchogram, lung consolidation, and bilateral pleural effusion. The subsequent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) revealed positivity for H5N1 and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)."

Conclusion:

"The H5N1 influenza virus is a cause of severe pneumonia. The clinical presentation of the patient had a predomination of H5N1 influenza rather than COVID-19. A PCR analysis for the identification of the virus is necessary to reveal the pathogen causing the severe pneumonia. The patient exhibited an excellent prognosis upon the use of the appropriate antiviral medicine."

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12879-023-08901-w

"Since 9 of 15 of the affected dairy herds in Michigan were closed herds which did not bring any new cattle into the herd, restriction of live cattle movements would not have prevented disease in these herds."

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/hpai-h5n1-dairy-cattle-mi-epi-invest.pdf