The School Engine Behind Flu and COVID — and Why Clean Air for Kids Is the Missing Public Health Tool

Every winter we treat flu season as if it were driven by weather, chance, or holiday travel. But when we compare this year’s flu season across the U.S., the U.K., Australia, and Japan — and especially when we compare this year to prior years — a very consistent pattern emerges.

Respiratory viruses don’t spread randomly. They spread through a structured transmission engine that links schools and homes together. Students infect classmates, bring infections home to siblings, and those siblings seed new classrooms in different grades and schools — creating a repeating loop that drives exponential growth. When that loop is interrupted, exponential growth stops.

This pattern is now visible across influenza, COVID, RSV, and other airborne viruses and bacteria — and it explains both why this year’s flu season rose so quickly and why it is now beginning to slow across much of the world.

TACT uses three simple hypotheses to describe this process.

TACT Hypothesis 1: Schools Ignite Exponential Growth

When a virus or other pathogen with a reproduction number (R₀) greater than 1 enters a school system, exponential growth becomes inevitable.

Classrooms combine high contact rates, repeated exposure, and a population with limited prior immunity. Infections move from students to siblings at home, then back into new classrooms — linking households and schools into a single high-throughput transmission network.

That is exactly what we saw this season.

The 2025–26 flu season is dominated by influenza A H3N2, subclade K — a strain that is antigenically distinct from last year’s mix of H1N1, H3N2, and influenza B. Subclade K spreads faster, appears more capable of reinfecting people, and partially escapes prior immunity. That antigenic “freshness” meant more people — especially children — were susceptible early, accelerating the surge.

Countries with earlier school terms and/or a higher base level of virus in circulation when schools opened saw the earliest waves:

• Japan peaked unusually early in the fall.

• The U.K. experienced high autumn and early winter flu activity.

• Australia saw one of its highest influenza seasons in years.

• The U.S. followed several weeks later.

The calendars aren’t identical, but the engine is.

This is not unique to flu. COVID, RSV, pertussis, measles, and other airborne pathogens follow the same pattern when immunity is incomplete.

TACT Hypothesis 2: School Breaks Stop Exponential Growth

When schools close long enough for infected students and staff to recover — usually about 10 days — the school-home transmission loop breaks.

The virus loses access to its most efficient pathway. Exponential growth stops. The curve begins to fall.

That’s why respiratory virus seasons almost always peak near late December and begin declining near January 1 — not after the holidays, but during them.

This holds across countries with synchronized winter breaks:

• The U.K., Japan, and much of Europe break for late December and early January.

• The U.S. does the same, though with more regional variation.

• Even in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia’s seasonal breaks play a similar role.

Travel can spread viruses. But it doesn’t create the dense, repeated, structured contact that schools do.

Travel redistributes infection.

Schools multiply it.

Once the multiplication engine is turned off, even high mobility can’t sustain exponential growth.

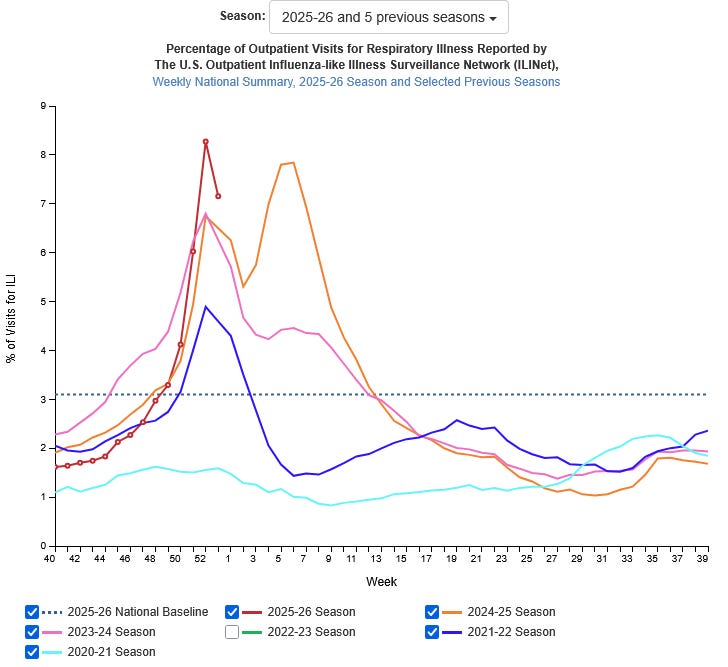

U.S. Outpatient Visits for Influenza-Like Illness Across Recent Seasons

This season of outpatient visits for respiratory illness went higher than prior years (in the red line) due to the influenza A H3N2, subclade K represented nearly 90% of all cases. Importantly, notice the recurring timing of the increasing number of visits and when the decline begins. This supports the conclusion that schools, not weather or holiday travel, are the primary driver of seasonal epidemic growth. While schools are in session, transmission between students and households fuels exponential spread. When schools close for winter break, that engine shuts down and cases begin to fall — often before or right at the start of the new year. Last season’s later peak reflects a slower burn across mixed strains and immunity patterns, not a different mechanism. The consistency of this pattern across years shows that epidemic timing is shaped more by social structure than by the calendar or climate alone.

TACT Hypothesis 3: After the Break, the Curve Resets

When schools reopen, transmission can restart — but from a lower baseline.

Most infected students have cleared the virus. Many now have immunity. The effective reproduction number drops below 1 unless enough susceptible people remain to reignite growth.

Last year, several countries saw a late-season rebound because immunity was more mixed and the virus burned through the population more slowly. This year’s dominant strain burned through susceptible children faster, producing earlier peaks and earlier declines.

Japan’s calendar is more synchronized, with fewer mid-winter breaks and a large spring break at the end of March. The U.S. calendar is staggered — February breaks in the Northeast and West, Mardi Gras closures in parts of the South, and spring breaks in March and early April — creating rolling local resets instead of one national reset.

But across all four countries, the same signal is now emerging: burnout — rising population immunity pushing transmission below sustainable levels.

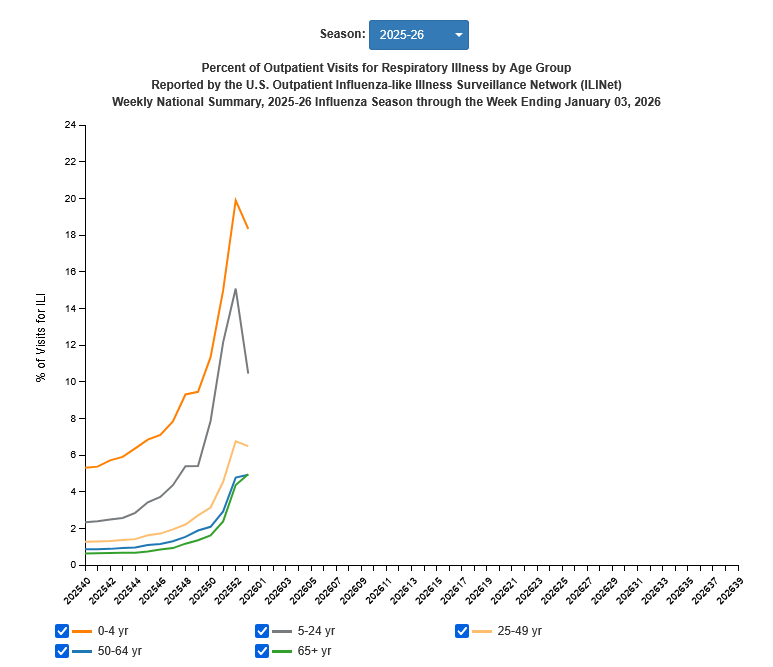

U.S. Outpatient Visits for Respiratory Illness by Age Group

This age-stratified pattern is exactly what we would expect if schools are the primary engine of exponential growth for airborne diseases. Children have the highest contact rates, the lowest prior immunity, and the greatest opportunity for repeated exposure in classrooms. Once that loop is broken — through school breaks or rising immunity — the epidemic collapses from the inside out. Pediatric cases fall first, then young adults, and finally older adults, reflecting the direction of transmission rather than independent outbreaks in each group. Reflecting the direction of transmission rather than independent outbreaks in each group. This same pattern appears across influenza, COVID, RSV, and other airborne infections, reinforcing that epidemic control depends on interrupting the school-based transmission network rather than reacting only after hospitals fill.

What’s Likely to Happen Next (U.S., U.K., Japan)

Using this model, the forecast for the next two months looks like this:

• Continued declines through February as immunity accumulates.

• Small regional rebounds where schools resume and susceptibles remain.

• Possible late-season influenza B activity.

• A return toward baseline by March and April.

A large sustained second wave is unlikely unless a new antigenically distinct strain emerges.

The Bigger Lesson: This Is About Air, Not Just Timing

The most important conclusion is not about this season — it’s about prevention.

These dynamics apply not just to flu, but to COVID, RSV, measles, pertussis, and other airborne infections. The same school-based transmission engine fuels them all.

That means we have a choice.

We can continue reacting every winter — accepting mass illness, overwhelmed hospitals, and preventable deaths — or we can interrupt the engine itself.

We don’t need school closures to do that.

We need clean air in schools.

High-quality ventilation, filtration, CO₂ monitoring, and properly maintained air purifiers can dramatically reduce airborne transmission without disrupting education or society. They turn classrooms from amplifiers into barriers.

Clean water ended cholera.

Seatbelts reduced car deaths.

Clean indoor air can do the same for respiratory disease.

We already have the tools. What we lack is the commitment to use them where they matter most.

If we protect schools, we protect communities.

And if we clean the air in classrooms, we can finally stop treating respiratory epidemics as inevitable. Support and Advocate for Clean Air for Kids

— TACT

Thank you for this piece. I shall add it to the toolbox to which I refer regularly when speaking in interviews, on panels, in friend or family circles, on social media, or in emails and letters to govt, public health, or organizations that clearly don’t understand this yet. It’s not the kids who are sick. It’s the structures they’re in that are sick.

Greetings Tact, I hope you’re having a good week.

I’ve been a silent observer of your posts for a while, and I just wanted to say thank you for interesting content.

You may enjoy one of my articles:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/health-history-and-fevers?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios