Avian Influenza A (H5N1) in Cats, Cows, and Humans: Symptoms, Timeline, Antiviral Therapies, and Vaccine Development - A Comprehensive Review

Key risks and prevention measures for avian influenza A(H5N1)

H5N1 Avian Influenza: A Critical Update

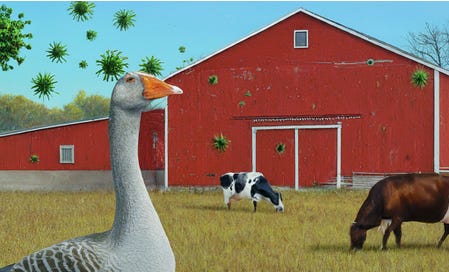

H5N1 has now been detected in dairy cows in multiple states in the United States. A human case in Texas linked to this outbreak underscores the potential for this deadly virus to jump species. Here's what you need to know.

What Is Avian Influenza?

Avian Influenza, also known as bird flu, is a highly contagious viral disease that has mostly affected domestic and wild birds. More recently it is infecting more mammal species, including humans. Beyond its impacts on animal health, the disease has devastating effects on the poultry industry, threatening workers’ livelihoods, food security, and international trade. The H5N1 strain is of particular concern due to its high mortality rate and the risk of adaptation allowing for easier human-to-human transmission.

Between 2003 and 2023, there were a total of 878 confirmed cases of H5N1 virus infection, resulting in 458 deaths, indicating a fatality rate of approximately 52%. Throughout this period, the majority of cases occurred in Asia and Africa, with notable hotspots in China (53 cases), Egypt (359 cases), and Indonesia (200 cases). From 2020 to July 2023, H5N1 infections in humans were reported in a variety of countries, including Laos (1 case), India (1 case), the United Kingdom (4 cases), China (2 cases), the United States (1 case), Vietnam (1 case), Spain (2 cases), Ecuador (1 case), Chile (1 case), and Cambodia (2 cases). These recent cases collectively resulted in more than three deaths. It's worth noting that this zoonotic virus has spread to new geographic areas, including South America. (1)

Currently, there is no evidence suggesting human-to-human transmission of the virus, however, with the growing rate of transmission among cows across multiple states, the risk of transmission to humans is increasing. The more humans infected, the greater the risk of viral evolution that could enable human-to-human transmission.

It's crucial to recognize that one of the deadliest influenza viruses in history, the Spanish influenza (1918–1919), originated from an avian influenza virus that adapted to infect humans. This occurred at a time when international air travel didn’t exist. The U.S. interstate highway system didn’t exist yet. This historical precedent underscores the importance of considering the potential for spillover when assessing the risk posed by the current virus.

Recent Developments

Infections in More Mammals: Since 2021, H5N1 has spread globally among wild birds, leading to infections in cats, skunks, goats, cows, and humans.

Second Human Case in the U.S.: In early April 2024, the second human case of H5N1 in the United States was reported in Texas. Thankfully, the individual exhibited only mild symptoms (conjunctivitis) and recovered after antiviral treatment.

We'll track the sequence of events involving H5N1 and examine the symptoms exhibited in humans, cows, birds, and cats, all of which have been affected by the virus. Additionally, we'll delve into the evolution of the virus, discuss potential vaccine candidates and treatments, and provide a comprehensive overview of the current situation.

Unlocking vital insights through exhaustive research demands considerable time and dedication. By becoming a paid subscriber, you not only gain access to exclusive content but also play a pivotal role in sustaining this critical endeavor. Join us in our mission by becoming a valued subscriber today, ensuring that crucial information remains accessible. While our ultimate aim is to provide unrestricted access for everyone, we require additional paid subscribers to cover essential expenses. A heartfelt thank you to our existing paid subscribers for their invaluable support!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to T.A.C.T. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.